This week’s parsha, Vayakhel, introduces one of the Torah’s most overlooked symbols: mirrors. The bronze basin used by the priests in the Mishkan was fashioned from the mirrors donated by Israelite women. Before performing sacred service, the priests had to wash there as a ritual reminder that moral authority begins with reflection.

Rashi (1040-1105) says these mirrors carried a deeper story. They were not instruments of vanity. In Egypt, when slavery crushed hope and dignity, the women used those mirrors to encourage their husbands and restore their spirit, and thereby build families that would become the nation of Israel. What appeared to be self-reflection was in fact an act of national responsibility.

Now Moses was about to reject them [mirrors] since they were made to pander to their vanity, but the Holy One, blessed be He, said to him, “Accept them; these are dearer to Me than all the other contributions, because through them the women reared those huge hosts in Egypt!” For when their husbands were tired through the crushing labor they used to bring them food and drink and induced them to eat. Then they would take the mirrors, and each gazed at herself in her mirror together with her husband, saying endearingly to him, “See, I am handsomer than you!” Thus they awakened their husbands’ affection and subsequently became the mothers of many children, – Rashi on Exodus 38:8

The Torah’s insight is timeless: using a mirror as a tool for the greater good. Individuals often avoid doing so. Nations, virtually never.

Spain today offers a vivid example of what happens when a country replaces the mirror with a flattering portrait of itself.

Spain presents itself as a moral voice on the international stage, particularly when it comes to Israel. Spanish officials speak the language of humanitarian principle and international law, portraying their stance as the product of ethical clarity.

But when viewed through the mirror the Torah describes, Spain’s posture looks far less like moral leadership and far more like moral performance.

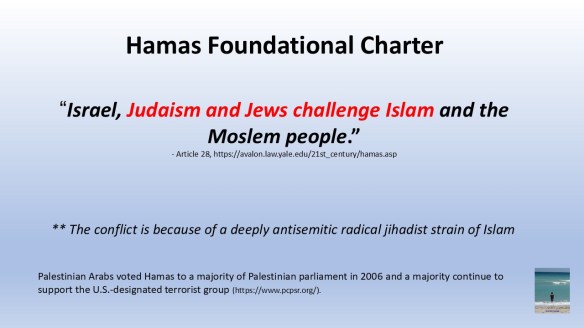

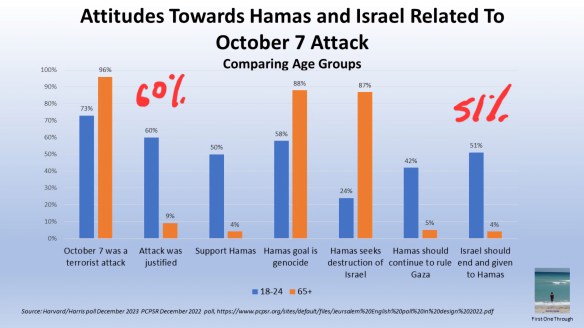

The issue is not disagreement with Israeli policy. Democracies criticize one another all the time. The issue is the enormous gap between Spain’s self-image and its conduct. Spain condemns Israel in sweeping moral terms while maintaining quiet relationships with regimes like the Islamic Republic of Iran whose human rights records make Israel’s conflicts look restrained by comparison. It speaks loudly about justice in the Middle East while applying far less scrutiny elsewhere.

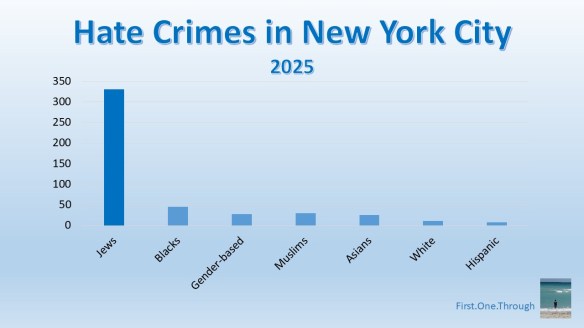

The mirror reveals something uncomfortable: a country congratulating itself for moral courage while directing its harshest condemnation toward the world’s only Jewish state.

This pattern does not arise in a vacuum. Spain’s relationship with Jews carries a long and painful history, culminating in the Alhambra Decree. The ease with which moral outrage is directed toward Jews while harsher regimes escape similar condemnation raises an uncomfortable question about whether some old instincts still linger beneath the surface.

The mirrors of Vayakhel represent the opposite instinct. The women of Israel used mirrors not to flatter themselves but to build a future. Their reflection demanded responsibility, not self-congratulation. That is why those mirrors became the basin in which priests purified themselves before entering sacred service.

The Torah’s message is simple: before claiming moral authority, look honestly into the mirror.

Spain seems to have replaced the mirror with a portrait of itself as a defender of justice. But to many observers the reflection looks different: moral preening, selective outrage, and criticism of the Jewish state so disproportionate that it begins to resemble something older and much uglier.

The basin in the Mishkan stood at the entrance to sacred service. Every priest had to wash there before speaking in the name of holiness.

Nations should consider doing the same.