Capitalism disciplines hatred only where it can still touch it. Where contracts exist, behavior can be checked. Where they don’t, mobs rule.

Kanye West (Ye) didn’t begin by attacking Jews. He began by denigrating Black people—calling slavery a “choice,” sneering at collective memory, mocking historical suffering. The reaction was outrage softened by indulgence. He was criticized, contextualized, excused. His Black identity functioned as camouflage. The lesson was clear: you could insult your own people and still be protected.

So Ye escalated. Antisemitism offered a bigger payoff—more visibility, more fear, more leverage. It worked until money intervened.

When Adidas cut him loose, the spell broke. Capitalism finally touched him and apologies followed—not from moral awakening, but because the incentive structure flipped.

This is often cited as proof that “the system works.” It doesn’t—at least not anymore.

Capitalism disciplines behavior only where value is concentrated. Ye had a centralized choke point: Adidas. Today’s antisemitism largely does not. It thrives where contracts don’t exist, boards don’t answer, and outrage itself is the reward.

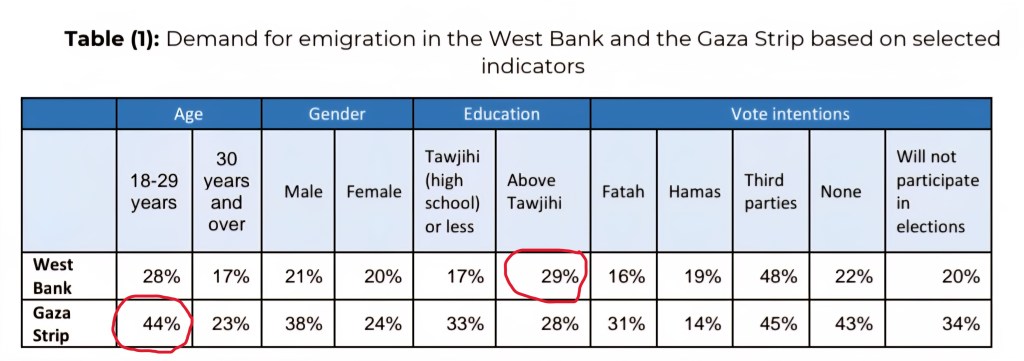

That vacuum has produced a new Ye-like template: antizionist Jews who denigrate Jews. They celebrate October 7. They call Israelis “Nazis.” They launder moral inversion through identity—and are absolved because of it. Jewishness becomes armor, converting bigotry into “bravery,” hatred into “critique,” massacre into “context.” The uglier the claim, the louder the ovation.

The center of gravity is social media—especially TikTok—where attention replaces contracts, outrage outperforms restraint, and individuals have nothing material to lose. There is no Adidas-scale counterparty. Condemnation becomes fuel. Challenge confirms righteousness.

This is where the political story locks in and takes flight.

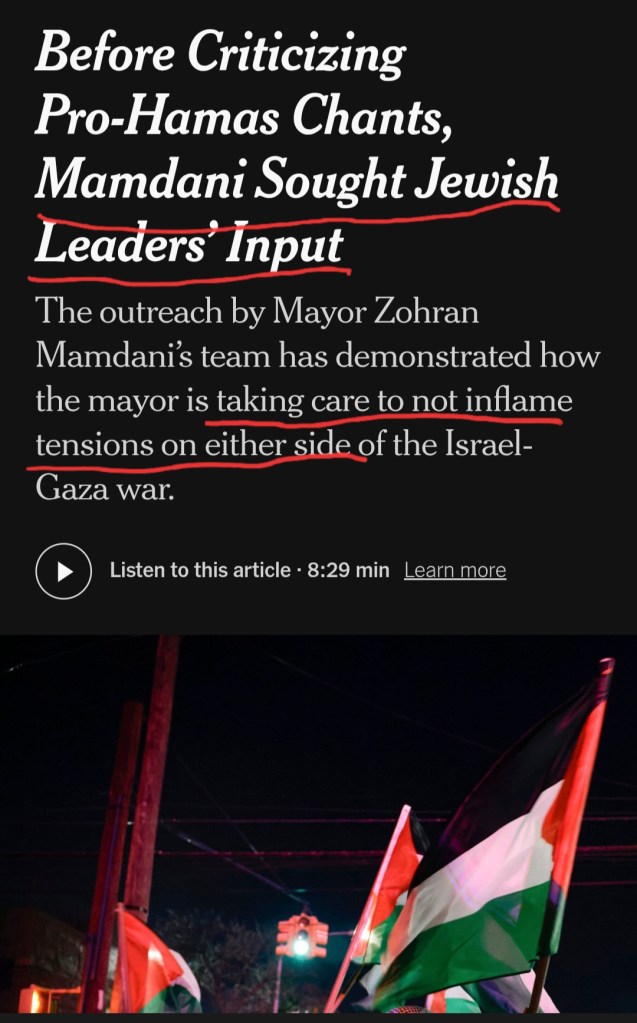

For years, the far left has discredited institutions under the banner of “corporate Democrats.” At the Democratic Socialists of America’s 2025 convention, a delegate said it plainly: the movement should organize people “that the corporate Democrats and Republicans have abandoned for dead.” In this frame, institutions aren’t imperfect—they’re illegitimate. Friction isn’t restraint—it’s oppression.

On the ground, the rhetoric sharpens. New York councilmember Alexa Avilés urged activists to “root out ‘corporate Democrats’ backed by AIPAC,” recasting pro-Israel Democrats as bought and disposable. Structural critique becomes moral license. Identity becomes proof. Mobs become “the people.”

Far-left media and politicians amplify the message—outlets like The Young Turks and figures such as Jamaal Bowman. They know that institutions impose friction > Friction slows mobs > Mobs hate friction. So the institutions must be delegitimized—and the most extreme voices elevated.

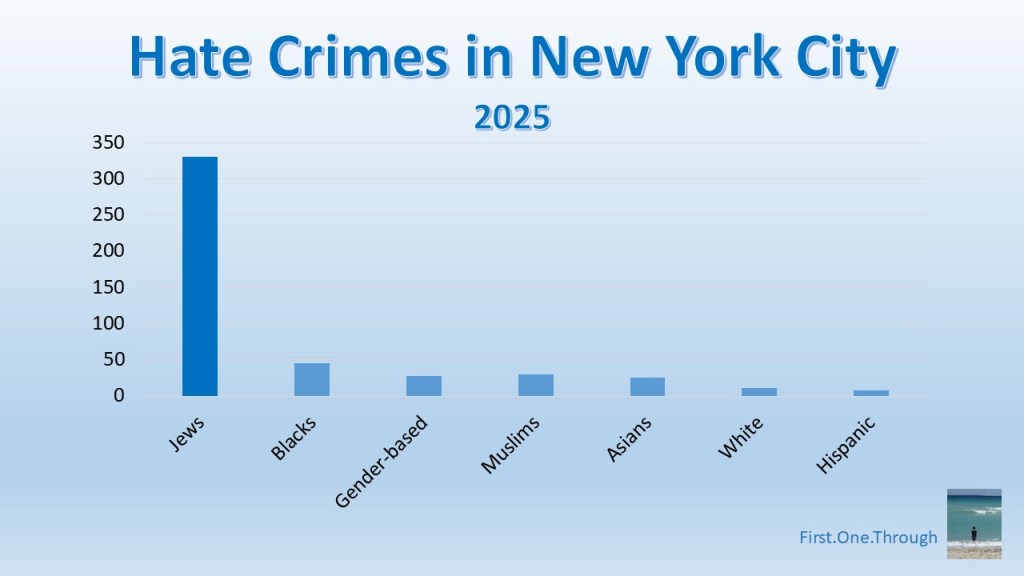

This is sold as empowerment. In reality, it is power to the algorithm. Algorithms reward the loudest, angriest, least accountable claims. In that environment, antisemitism doesn’t just survive; it thrives. Jews are too small a minority to outvote a mob optimized for rage.

The reality is that capitalism was never the moral engine here, but it was sometimes a brake. Contracts could snap shut and money could impose limits. When those limits vanish—when speech floats free of consequence and identity shields cruelty—nothing restrains the mob.

Ye was stopped because capitalism still touched him when he crossed from trashing Blacks to bashing Jews.

The antizionist Jewish influencers celebrating October 7 are not stopped because nothing touches them. In People Capitalism, attention is the asset, outrage is the yield, and antisemitism is rewarded, and boosted on a litter—especially when Jews attack Jews.

Every such system needs a moral absolver.

That role is played by Bernie Sanders—the mob’s messiah. He doesn’t organize the mob; he legitimizes it by claiming it isn’t radical, reframing rage as righteousness by declaring institutions corrupt, restraint oppressive, and “corporate Democrats” illegitimate. His function isn’t governance. It’s permission to come for mainstream Democrats and other Jews.

This is the final logic of People Capitalism:

- markets once imposed limits; crowds impose none.

- institutions once punished bigotry; mobs reward it.

When the people become the market, antisemitism becomes a ladder—

and the mob’s messiah has sanctified the climb.