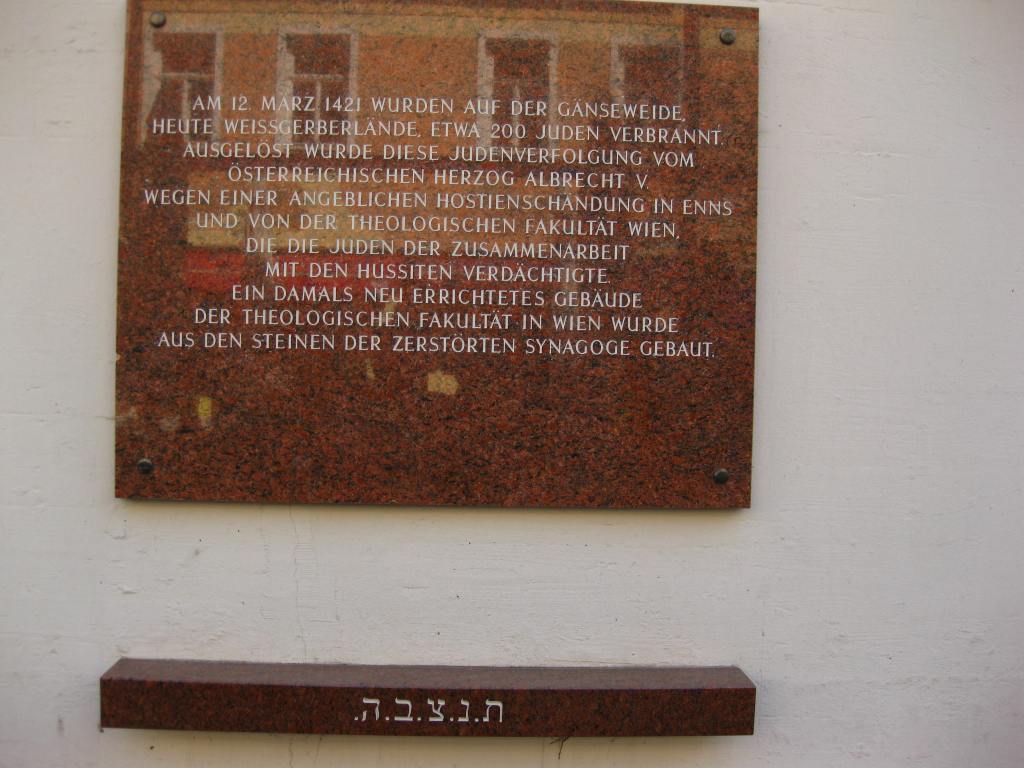

The near-term ramifications of Hamas’s war against Israel are being crystalized. Hamas’s leadership is decimated and Gaza is in ruins. The political-terrorist group’s allies in Lebanon, Syria, Iran and Yemen have been dealt severe blows, perhaps fatal for some. Hamas’s cheerleaders in the Global North are the only ones to have gathered momentum, particularly in Australia and the United States where hunting season for Jews has a seemingly open permit.

To gain insight for the next tactical steps, world leaders are looking at the current situation and polls since October 7, 2023 and have drafted proposals and taken initial actions: The United Kingdom and Canada recognized a Palestinian State. The U.S.’s Trump administration put forward a plan for Gaza which would include a new governing entity. The West hopes that the targeted assaults and murder of Jews will peter out along with the end of war. And the United Nations keeps playing the same tune about supporting UNRWA.

These are bad decisions and conclusions, made on faulty assumptions.

There is an organization that has been polling Palestinian Arabs for decades, called the Palestinian Center for POLICY and SURVEY RESEARCH (PCPSR). It conducted a poll of Arabs in Gaza and the West Bank, just before the Hamas-led war, from September 28 to October 8, 2023. Because of the war, the results did not get published until June 26, 2024, and the world was too focused on the war to pay it any attention. It is deeply unfortunate, and it is required reading to help chart a better future for the region.

To start with the poll’s conclusions:

- A large percentage of Palestinian Arabs have wanted to leave Gaza and the West Bank for years, not from the current destruction

- Arabs are fed up with their own government – Hamas and the Palestinian Authority – much more than Israeli “occupation”

- Canada is viewed much like Qatar for Gazans, a sympathetic haven

Palestinian Arabs Wanted to Emigrate Before the War

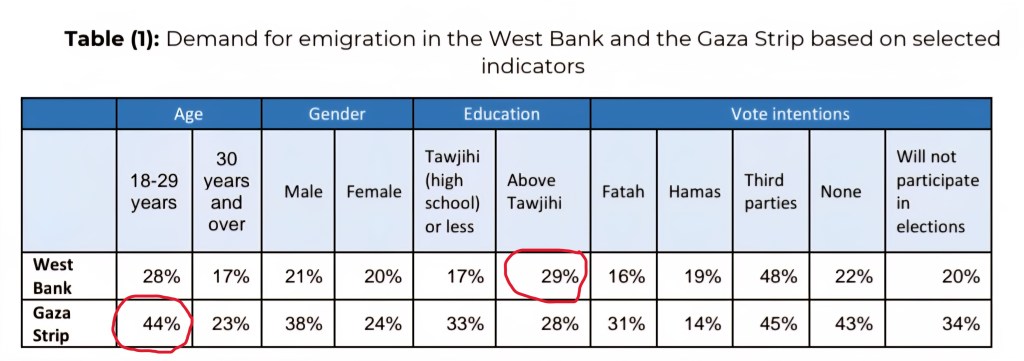

According to PCPSR, whether in October 2023 or November 2021, roughly 33% of Gazans and 20% of West Bank Arabs wanted to leave the region.

Men below age 30 make up the vast majority of those seeking to emigrate. As opposed to Gaza where both educated and uneducated people want to leave, it is the educated West Bank population that wants to move away. Among those wishing to leave, many would not vote in Palestinian elections, or if they would, they would sooner vote for third parties over Fatah or Hamas.

Palestinian Leadership is the Curse, More than Israel

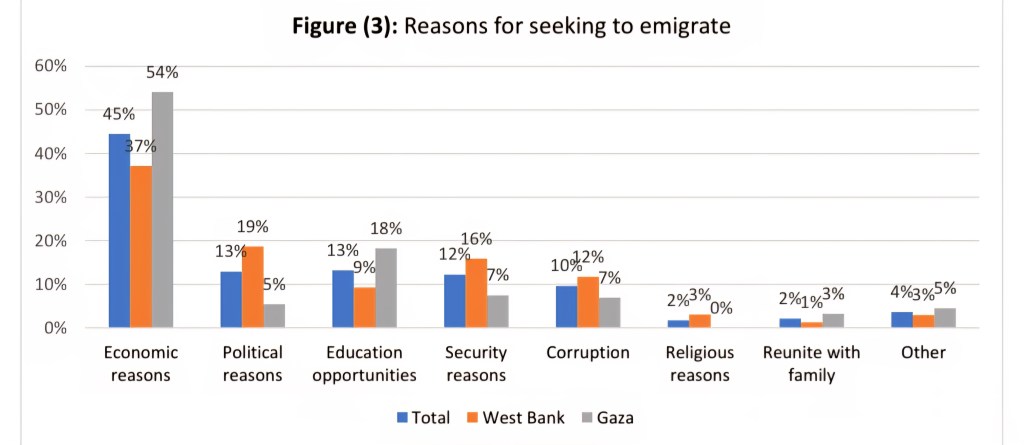

The number one reason for wanting to leave was economic conditions by a far margin. Reasons two and three were political reasons and educational opportunities. “Security reasons” came in fourth, with only 7% of Gazans focused on security; 12% overall. Corruption, religious reasons and to reunite with family rounded out the poll.

Canada as a Beacon

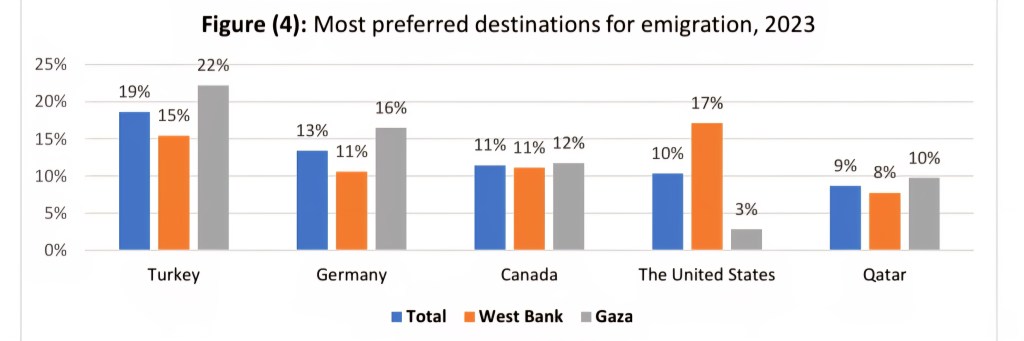

Turkey and Germany were the two most favorite destinations, especially for Gazans. Very few Gazans (3%) considered the United States, while West Bank Arabs put it as the number one choice (17%), likely seeking advanced degrees at left-wing universities. What is remarkable, is more of the Stateless Arabs (SAPs) would prefer going to Canada (11%) than Qatar (9%), the wealthy Muslim Arab nation that is a main sponsor of Hamas.

Honest Takeaways

These pre-war results leads to some basic and critical conclusions.

- Complete Overhaul of Palestinian leadership, not just in Gaza

The desire of Arabs to leave was evident across both Gaza and the West Bank for many years. This was not a reaction to bombing or siege; it was a verdict on governance.

Hamas in Gaza rules through repression, diversion of aid, and religious militarism. The Palestinian Authority in the West Bank offers corruption, authoritarianism, and political stagnation. Together they have produced a society with no credible economic horizon, no accountable leadership, and no peaceful mechanism for change.

While a new entity is needed to administer Gaza, that role should be akin to a Chief Operating Officer overseeing construction. The Palestinian Authority itself needs to be gutted and rebuilt as it is a corrupt, unpopular and ineffective entity.

- The United Nations Must Withdraw from Gaza and the West Bank

In its desire to create a Palestinian state, the U.N. has stripped the titular heads of Palestine of any responsibility. The UN protects Hamas despite its savagery. It props up the Palestinian Authority despite its rampant corruption. Palestinian leadership is a bed of paper scorpions.

The UN must withdraw from Gaza and the West Bank and allow local authorities to build a functioning leadership team.

- The West Should Rescind Recognition of Palestine

There is no functioning Palestinian government and therefore no basic standard to recognize a Palestinian State. The United Kingdom, Australia and others should withdraw their recognition and make it conditional on building governing institutions that can lead and make peace with the Jewish State next door.

- Reeducation in the West

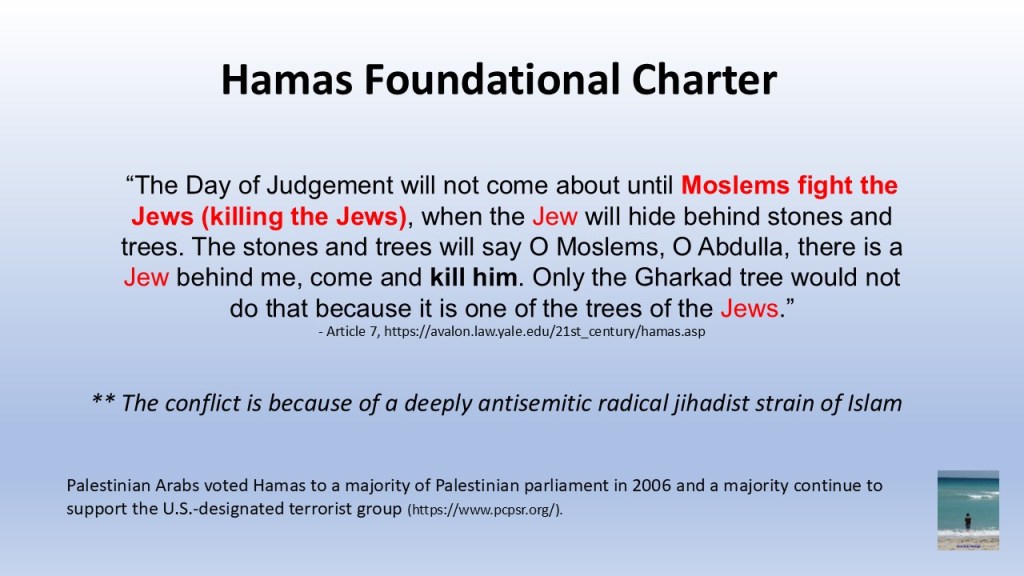

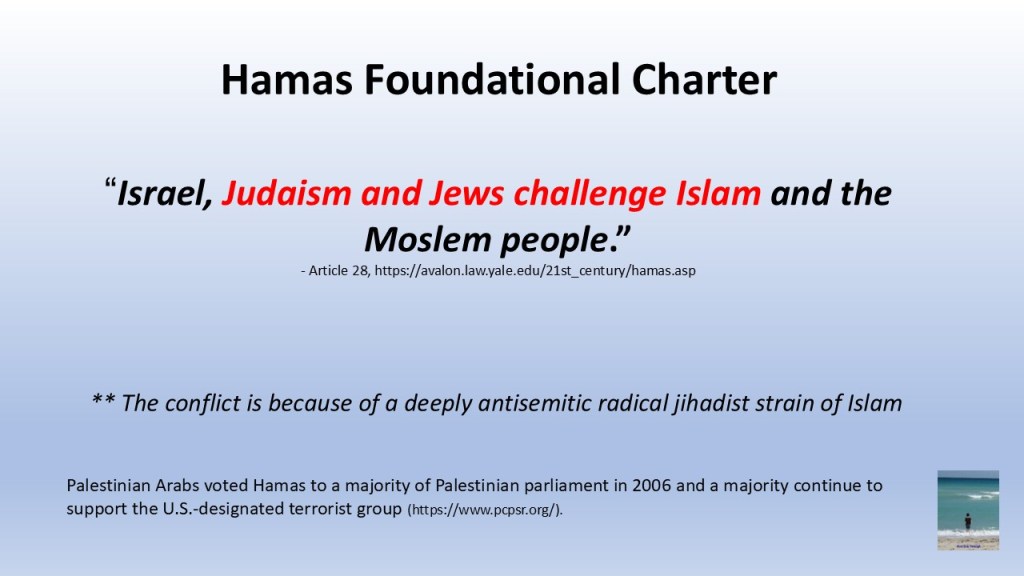

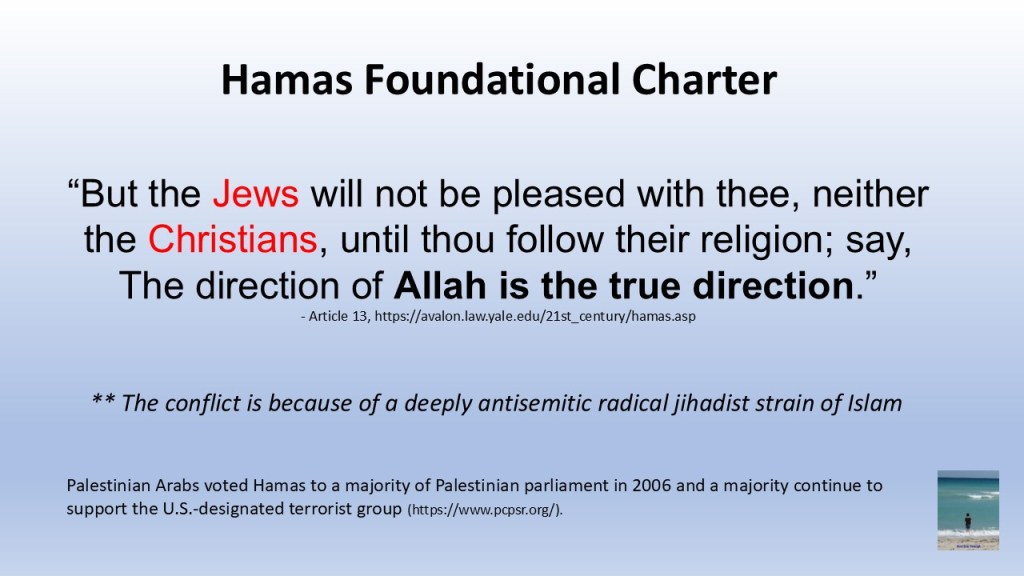

The massacre did not arise from a sudden spike in pressure. It emerged from long-standing internal failure. Hamas chose atrocity because it couldn’t commit a complete genocide of Jews so exploited its own population to be fodder for Israel.

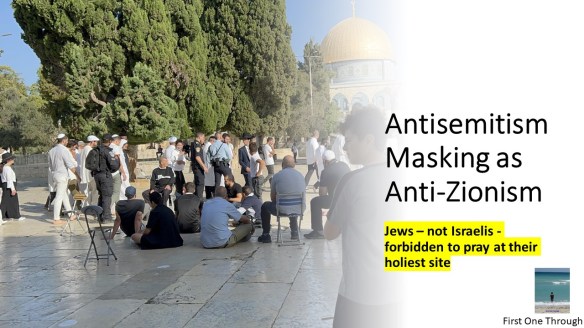

Western audiences were then handed a familiar script, complete with pictures. But the data taken just before the massacre tells a different story—one far more consequential. What is being taught in western public schools is divorced from reality and feeds global and local antisemitism.

- Oh No, Canada

While the fears of antisemitism are focused on the United States and Australia because of recent attacks on Jews, Canada is in the hearts and minds of Palestinian Arabs seeking a warm diaspora community. Perhaps it started a decade ago under Justin Trudeau who followed U.S.’s President Barack Obama to embrace the Palestinian cause and Iranian regime over Israel. Perhaps it is because of the welcome mat for extremists groups like Samidoun. Or perhaps it is the perception that the heckler’s veto is fair game, and can run Jewish families off Canadian streets.

Whatever the inspiration, Canada is widely perceived as permissive, ideologically indulgent, and administratively porous—an attractive environment for “political activism” untethered from civic responsibility. It is a ticking time bomb.

The poll of Palestinian Arabs on the eve of the October 7 war reveals deeper truths than surface shots of leveled homes. The PCPSR findings point to a single truth: the Palestinian problem is fundamentally internal.

Ending Israeli control over territory without dismantling corrupt and extremist institutions will not deliver prosperity or peace. Statehood layered on top of dysfunction will harden it. And exporting populations shaped by jihadist rule into permissive Western societies without serious screening and integration, risks importing instability rather than relieving it.