People assume the moon is a universal constant. A simple shared celestial orb rising and falling across planet Earth.

At first glance, that seems right. The phases of the moon follow the same cycle for everyone. The waxing crescent in New York is the waxing crescent in Nairobi. The full moon bathing Buenos Aires is the same one brightening Beijing.

But the details betray the simplicity.

Because of Earth’s curvature and tilt, the angle of the moon changes depending on where you stand. In the northern hemisphere, the crescent opens to one side; in the southern hemisphere, it opens to the other. Near the equator, the crescent often lies on its back like a cup collecting light. The horizon line shifts the moon’s ascent and descent, making the same moon feel subtly unfamiliar across latitudes.

So while the moon itself is constant, the human experience of it is not. Geography shapes perception.

Which brings us to a particular location: Jerusalem.

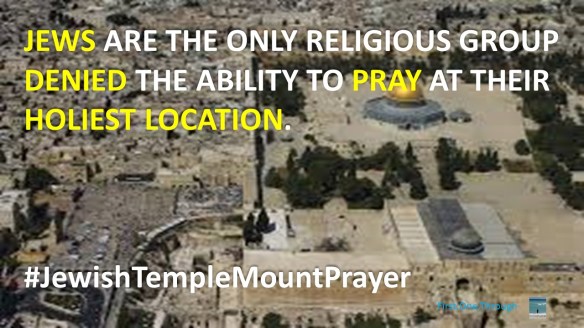

Why did ancient Jewish sages insist that the new month—the very heartbeat of the Jewish calendar—could only be declared there? Why could only witnesses standing in that one city testify that they had seen the first thin sliver of the new moon? It wasn’t because Jerusalem had the sharpest skies or the best astronomical vantage point. Other regions had clearer air, lower humidity, more favorable horizons.

The choice was not scientific. It was cultural.

The sages understood that if the Jewish calendar were anchored anywhere else—in Babylonia, in Alexandria, in Rome—it would become a local calendar. A diaspora calendar, and reflection of exile. Time would belong to the places where Jews merely lived, not the place where they belonged.

And so they declared: the Jewish month begins only where Jewish destiny begins.

In Jerusalem.

The moon in Jerusalem is not visually unique. It does not shine brighter, hang lower, or reveal a different pattern of craters. What is different is what it carries.

Elsewhere, the moon is a mechanism of light in the night. In Jerusalem, it is a messenger and message.

In the city, it rises over stones worn by millennia, over a city that has been destroyed and rebuilt and prayed toward more times than any other on earth. Outside of Jerusalem, generations of Jews looked to that moon to mark the days of their wandering. Prisoners in Soviet cells whispered its phases in the dark. Families in medieval Europe and North Africa opened their windows each month hoping for a sliver that someone in Jerusalem might already have seen.

For them, the new moon was a signal: Somewhere, in the city we lost, time is still ours.

The moon is the same everywhere, but meaning is not. For Jews, the appearance of the moon in Jerusalem was the moment when wanderers and exiles, merchants and mystics, shepherds and scholars all re-entered the same story, no matter how far they lived from its setting, regardless of their own particular vision of the moon.

The world sees a reflection of the sun’s light in the moon. Jews see a reflection of their unique common heritage, and permanent tie to Jerusalem.