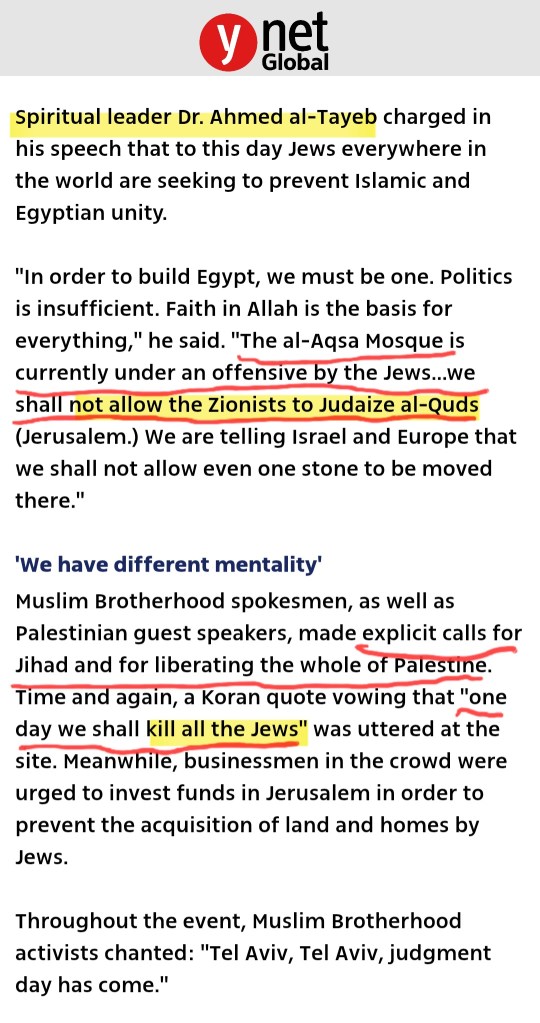

There are many forms of antisemitism. This review is about religious antisemitism, specifically from Christians and Muslims.

As a clear disclaimer, not all Muslims or Christians hate Jews. Or the Jewish State. But there are undeniable fundamental differences in how religions perceive each other which are sometimes caustic.

The world often describes the three great monotheistic religions together: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. But lumping Jews with the other two faiths leads people to falsely put the three on the same plane. There are roughly 2.2 billion Christians and 2.0 billion Muslims today, compare to only 15 million Jews. To give the scale some perspective, if people of the three faiths were in a stadium, all the levels of half the stadium would be Christians while the other half would be Muslim, with Jews only wrapping the entrance portals for the players.

Christianity and Islam are global religions – they have brought their faith to the far corners of the world by sword and missionaries. But Judaism is more akin to a local tribal religion in Africa or South America. The faith is tied to a specific piece of land – the land of Israel. Jews do not seek to convert people or believe non-Jews are destined to eternal damnation unless they follow the same belief system.

When Muslims and Christians conquered / invaded / colonized the Americas and Africa, they believed they were helping people by spreading a faith the locals had never heard of. One cannot blame an Amazonian tribe for not believing in Jesus when they never heard of him. One cannot immediately hate the local African tribe for not believing in Mohammed when the name and faith were brand new.

But Christians and Muslims cannot say the same of Jews. Their faiths share a common history.

Jesus was a Jew who lived in the land of Israel. Mohammed was an Arab, a descendant of the same forefather Abraham who is also the forefather of Judaism.

For devout Christians and Muslims who feel that spreading their faith is integral to their belief – a form of religious supremacy – Jews are forever a stiff-necked people who refuse to join the global masses and appreciate the true prophets.

So how, when and why did the Jews become so stubborn?

In the biblical parsha of Ki Tisa, the Jewish nation was called a stiff-necked people several times – by God. When the people became worried that Moses had disappeared and made themselves a golden calf idol, God said to Moses:

“I have seen these people,” the Lord said to Moses, “and they are a stiff-necked people.” – Exodus 32:9

The phrase is meant as a criticism that Jews cannot get out of their old habits and will not be able to adopt the new laws that God has set out for the nation. The phrase appears repeatedly, including:

- “Go up to the land flowing with milk and honey. But I will not go with you, because you are a stiff-necked people and I might destroy you on the way.” – Exodus 33:3

- For the Lord had said to Moses, “Tell the Israelites, ‘You are a stiff-necked people. If I were to go with you even for a moment, I might destroy you. Now take off your ornaments and I will decide what to do with you.’ – Exodus 33:5

- “Lord,” he said, “if I have found favor in your eyes, then let the Lord go with us. Although this is a stiff-necked people, forgive our wickedness and our sin, and take us as your inheritance.” – Exodus 34:9

The last quote is from Moses to God, in which he uses the same language God invoked. But Moses argues that the trait should be and will be their salvation. He argues that they need more of God’s compassion than others because of their nature, and once they know God and learn the commandments, they will become affixed forever.

Just as the Jews were becoming a nation, God was worried about their stubborn nature, but Moses assured God that the same trait will make them a holy nation forever that deserved forgiveness and the promise of internal inheritance. That same stubborn trait has kept the Jews alive, distinct, and small, for thousands of years, an easy group to ignore or appreciate on a global scale, or a perpetual irritant for those who cannot enjoy humble faith, and demand religious superiority over this small ancient people.