On December 8, 1965, a crowd of 100,000 spectators assembled in St. Peter’s Square to mark the closing ceremony of Vatican II. The three years of work was orchestrated to bring about Christian unity, hoping to bring non-Catholics and Catholics together in a joint mission. The sixteen documents that the council enacted were designed on the theme of aggiornamento (Italian for bringing up to date) the Catholic church, which had started to be viewed by many as fading in relevance.

The Second Vatican Council did not emerge in a Christian vacuum. It unfolded in the long shadow of Auschwitz, under the moral weight of a truth that could no longer be hidden: Christian Europe had stood by, silent or complicit, as the Jewish people were hunted, deported, and incinerated. The murderers were not pagan invaders; many were baptized Christians. The trains did not run through lands hostile to Christianity; they passed churches, crossed Catholic villages, glided along tracks laid in the heart of Christendom.

In 1961, the world could no longer avert its eyes. The Eichmann trial in Jerusalem forced every nation, every church, every conscience to watch. Survivors spoke in court with the clarity of witnesses resurrected from the grave: the collaborators, the bystanders, the bureaucrats, the bishops who said nothing, the priests who closed doors, the institutions that rationalized their silence. The trial tore away the last veil protecting Christian moral innocence. It was a moment when the Church had to confront not only the sins of individual Christians but the theological soil in which hatred had grown.

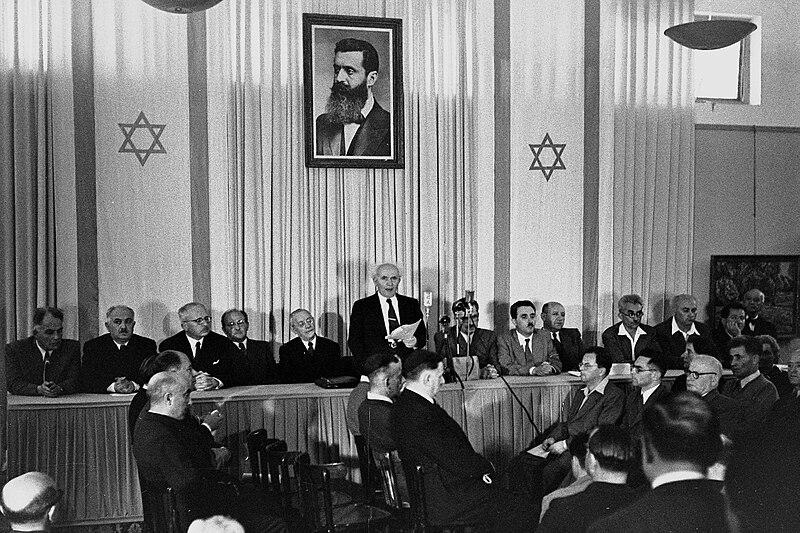

Against this storm of reckoning, another seismic event had already taken place: the re-establishment of the Jewish state in 1948. For nearly two thousand years, Christianity had preserved an image of the Jew as the wandering witness, condemned by God to homelessness so Christians could inherit the promise. But suddenly, the wandering stopped. The Jewish people returned to their ancient homeland. Hebrew was resurrected from liturgy into daily speech. Jewish sovereignty reappeared as if history itself had refused to obey the theological script.

Israel’s rebirth shattered the Christian narrative of Jewish exile more forcefully than any sermon ever could. It reopened questions buried since the early Church Fathers: What does it mean if God’s covenant with the Jews never ended? What does it mean if the Jewish people still live, still dream, still return? What does it mean when prophecy looks suspiciously like news?

By the time the Vatican convened, the Church was wrestling with two cataclysms: the moral collapse of Christian Europe during the Holocaust and the miraculous revival of the Jewish nation that Christian theology had relegated to the margins of history. These two realities — failure and fulfillment — created an impossible tension.

One of the sixteen Vatican II documents, Nostra Aetate (October 26, 1965) was not merely a doctrinal correction. It was a confession, an apology, a theological revolution. It declared the Jews not rejected but beloved, not guilty but enduring, not a fossil but a living partner in covenant. It rejected antisemitism “at any time and by anyone.” For Christians, it was liberation from a poisoned inheritance. For Jews, it was an unexpected invitation to be seen — perhaps for the first time — not as shadows in another people’s story, but as a people with a story of their own.

And something else began in the wake of Vatican II, something few would have predicted: the rise of Christian Zionism in its modern form. Many Christians, freed from the contempt of supersessionism, looked upon the Jewish state not as an accident of geopolitics but as a fulfillment of ancient promise. Some of Israel’s strongest supporters today come from Christian communities shaped by the theological revolution Vatican II inaugurated. They see Jewish sovereignty as evidence not of colonialism but of covenant, not of power but of destiny. They stand with Israel not out of political calculation but out of spiritual gratitude — an act of repentance and solidarity woven together.

For Jews, this support has been both a blessing and a riddle. After centuries of persecution in Christian lands, how does one accept the embrace of former adversaries? How does a people long defined by suspicion learn to trust a hand that once struck but now extends in friendship? The Jewish story, once shaped by surviving Christian hostility, must now grapple with receiving Christian loyalty. The sting of history meets the strange balm of reconciliation.

These questions unfold in a nation — the United States — whose own identity has been shaped by Judeo-Christian roots from its earliest days. As the country approaches its 250th birthday, Americans are rediscovering that its foundational ideas — human dignity, moral law, liberty of conscience — flowed from a biblical inheritance shared by Jews and Christians alike. The Founders read the Hebrew Bible not as relic but as roadmap. The Exodus shaped the imagination of revolutionaries and abolitionists. The prophets shaped the conscience of Lincoln and King. The Jewish story is woven into the American one, even when America failed to honor it.

Now, as antisemitism again rises and institutions fray, the old alliance becomes newly urgent. Jews and Christians are bound not by accident but by destiny: two peoples who share scripture, share moral vocabulary, and share responsibility for sustaining a civilization built on covenant rather than empire. Vatican II made it possible for this bond to be spoken aloud again, freed from the hostility that had once obscured it.

December 8, 1965 created a new Christian. But it also created a new Jew: a Jew who could stand in relationship not only to Jewish history but to Christian history, not only in resistance but in dialogue, not only as survivor but as partner. A Jew whose identity could be affirmed by the very institutions that once erased it.

And perhaps, as America steps toward its 250th year, this renewed bond is not merely theological or historical. It is a reminder that the future of Western freedom may depend on the same truth Vatican II finally proclaimed: that the Jewish people are not a footnote in someone else’s story, but the root from which so much of our shared moral world has grown.