Four university presidents of America’s leading academic institutions came to the United States capital to address a congressional hearing on antisemitism on college campuses. Most failed to satisfactorily answer a very simple question: “Does calling for the genocide of Jews violate the school’s code of conduct?” As private institutions, the question had nothing to do with free speech, and in framing the question about “the genocide of Jews”, there was no debate about what “intifada” or “Free Palestine” meant.

The answers should have been clear and unambiguous, just as if the question were about students shouting to drown gay people or lynch Blacks.

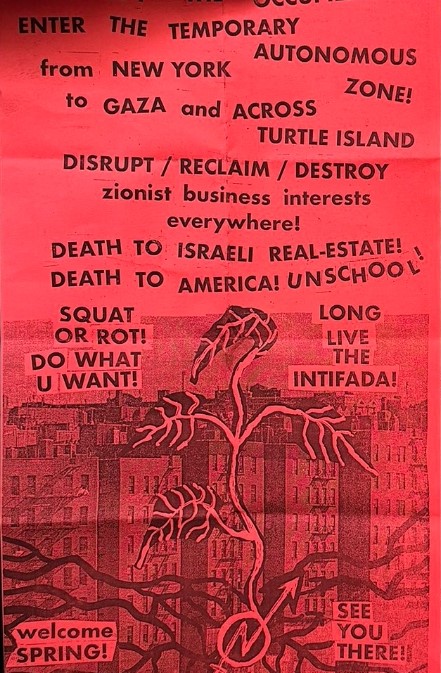

Not long after America’s theoretically best-and-brightest failed Morality 101, campuses around the country actually began calling for the genocide of Jews and the destruction of America. Right in New York City, the capital of Diaspora Jewry, people called for a repeat of the October 7 massacres, to kill Zionists and Israeli businesses and to run Jewish organizations out of the public square.

Somehow, this has caught New Yorkers and Americans off guard, as if October 8th happened from thin air. As if there had not been antisemitism and anti-Zionism in the United States. As though the situation for American Jews was at perfection on October 6.

This dynamic recalls the story of the Jews in Persia 2,500 years ago, as told in the Book of Esther. Hints about the current tragedy are laid out in how the story is chanted in synagogues.

That story, retold on the holiday of Purim, began to unfold around the year 483BCE. The Jewish exile had come to a close with most Jews having returned to the land of Israel after the First Temple was destroyed one hundred years earlier. Still, many Jews decided to remain in the Persian kingdom in the Jewish diaspora, as their lives had become quite good.

As laid out in chapter three, there was an opportunist named Haman who saw that the laws of the land were capricious. In that backdrop, he saw a wealthy, non-conformist community that was easy prey and offered the king 10,000 talents of silver in exchange for the fate of the Jews. Every single Jew – from infants to the elderly – were to be exterminated, leaving no heir for Haman to consider as he stole the lives and property from every unsuspecting Jew, yielding himself multiples of the 10,000 talents of silver.

The edict against the Jews was not made in secret. It was put in public in every province and every language. At the end of the chapter, the text states that the king and Haman sat down together “but the city of Shushan (the capital) was bewildered.”

The Book of Esther is sung in a unique set of happy cantillations, but there are a few parts that are read in an unhappy melody used for the Book of Lamentations. One would imagine that the entirety of chapter three describing the condemnation of the country’s Jews for annihilation would be read in the sad tune, but it is not. Only those last few words “the city of Shushan was bewildered” are sung in the sad melody.

Why? Why would the rabbis leave the call to annihilate Jews in a happy tune but the dumbfoundedness of Jews and non-Jews of Shushan emphasized in tragic song?

There are a few explanations.

Some suggest that the Persian Jews should have moved back to the land of Israel. That foreign laws turning on Jews should not be shocking. The Persian Jews had deluded themselves that they were living in the heart of civilization in a protected lifestyle. It was that delusion and failure to return to the holy land that was the tragedy; the new antisemitic edicts were to be expected.

Another approach builds on that theme. Jews had become trained to only think of antisemitism in a certain way: the blocking of particular rituals like kosher, observing the Sabbath and circumcision. If those were practices were not infringed upon, the general breakdown of a legal framework in the country was ignored.

These ideas are familiar to Jews in America today.

American Jews were trained to think of society as not inherently antisemitic because their synagogues got built and they attained corporate success. While they saw the reports that Jews suffered the greatest number of hate crimes, it was generally dismissed as being a problem for the outwardly devout, while those focused on just living and working with their heads down would do just fine.

Jews ignored politicians saying that wealth is in the hands of the “wrong people.” They didn’t complain when edicts for DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) specifically excluded Jews and promoted other minorities. Jews observed themselves being systematically removed from positions of power and joined the celebration; diversity replaced meritocracy, seemingly in line with “social justice” and “tikkun olam“, even if not universally fair.

Somehow, it never dawned on American Jews that they were facing a threat as they watched a legal and financial system which was based on fairness and hard work in which they participated and excelled, being trashed as inherently racist. Jews nodded approval that a proper response to the War on Terror on a couple of Muslim-majority countries was to facilitate billions of dollars and tens of thousands of students and professors from other Muslim-majority countries into leading American universities. They did not consider that the curricula was being gutted to vilify America, capitalism, Jews and the Jewish State.

America and American Jews – like Persia and Persian Jews 2,500 years ago – were duped into believing that antisemitism was only about Jewish customs and ignored the reality that the seeds of antisemitism are planted when a legal framework that protects EVERYONE is dismantled in favor of a select few. More specifically, laws that excluded Jews in favor of people of preference.

To be bewildered is to be caught off guard, a horribly sad situation for a people who have thousands of years of history from which to learn.

Related articles:

Politicians In Their Own Words: Why We Don’t Support Defending Jews (January 2022)

The Wide Scope of Foreign Interference (November 2020)

Pelosi’s Vastly Different Responses to Antisemitism and Racism (June 2020)

The Building’s Auschwitz Tattoo (April 2020)

The March of Silent Feet (January 2020)

Anti-Semitism Is Harder to Recognize Than Racism (September 2019)

From “You Didn’t Build That” to “You Don’t Own That” (August 2019)

I See Dead People (July 2019)

The Holocaust Will Not Be Colorized. The Holocaust Will Be Live. (May 2019)

Watching Jewish Ghosts (March 2018)

Your Father’s Anti-Semitism (January 2017)