The story at the end of the Book of Genesis has an interesting lesson for Jews today.

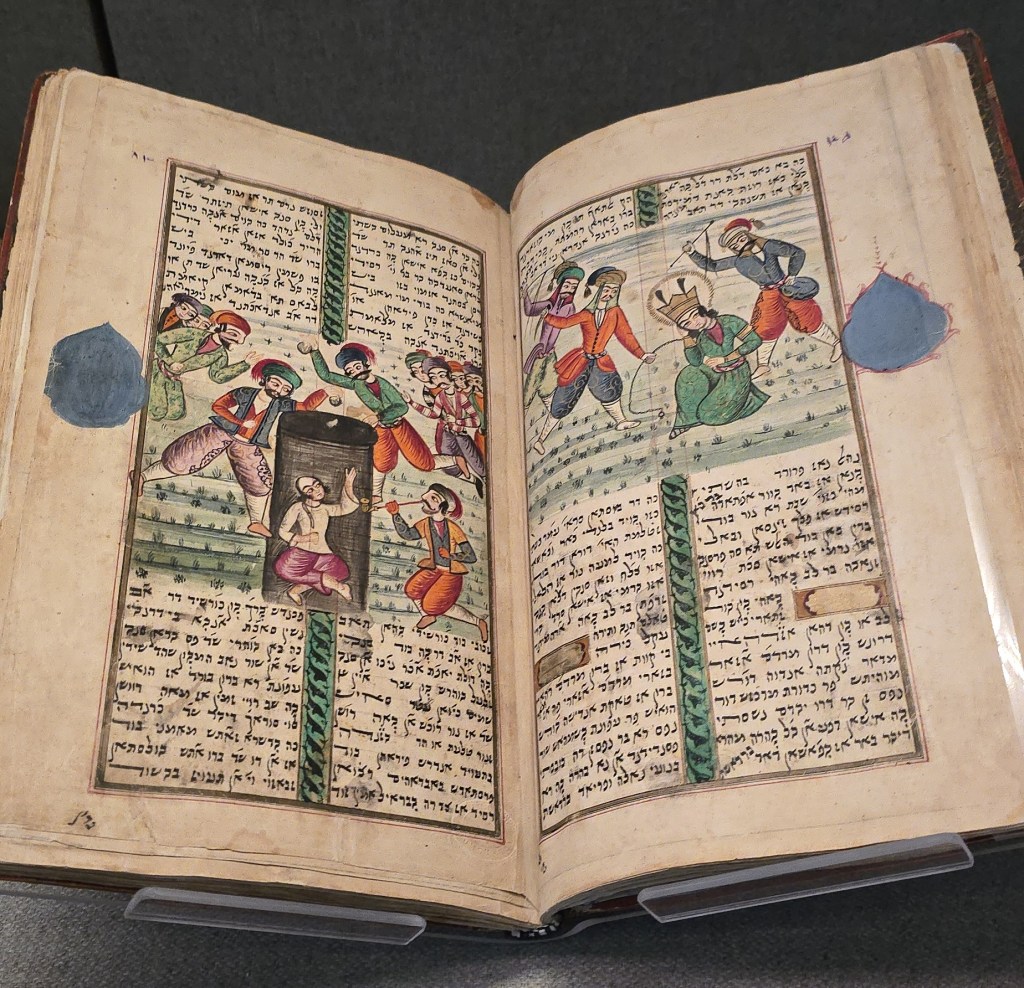

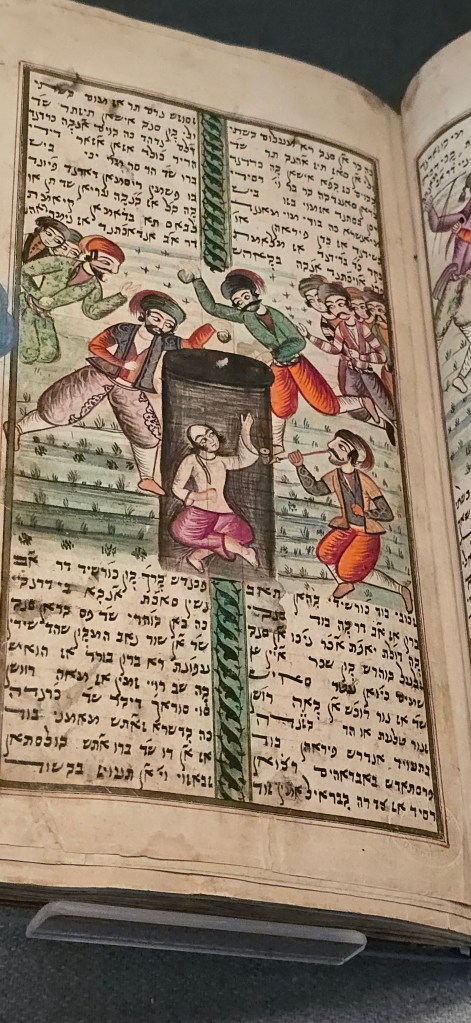

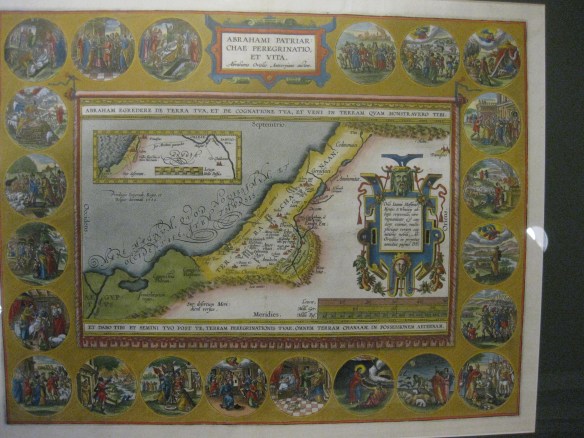

If Jacob’s sons had remained in Canaan, the biblical pattern likely would have continued unchanged. Land and cattle anchored wealth, security, and continuity, and survival depended on concentration. In such an environment, inheritance narrowed toward a single heir capable of holding territory together through famine and conflict. Until this point, Genesis follows that logic closely, moving from Abraham to Isaac, from Isaac to Jacob, and nearly from Jacob to Joseph.

Canaan seemingly reinforced singular succession.

Egypt reshaped it.

The famine drained land of its defining value and redirected survival toward provision. In Egypt, Goshen mattered because it was allocated rather than owned. Jacob’s family entered as dependents, albeit under the protection of a senior official. With land no longer functioning as the primary store of value relative to neighbors, inheritance lost its organizing role. What carried forward instead was character and capacity.

Jacob recognized the shift and adapted to it. His final blessings did not distribute assets or authority but identity. Leadership, resilience, intensity, cohesion, adaptability—each son was seen for what he could contribute rather than what he would receive. Blessing became formative rather than transactional, oriented toward coexistence rather than accumulation.

This evolution reflected Jacob’s own hard-earned understanding. Early in life, he secured a singular blessing that concentrated destiny in one person and fractured a family in the process. Now, with seventy descendants – coming from different mothers – preparing to live together under pressure, he understood that continuity required a new orientation. Blessings and inheritance had to evolve if brothers were going to coexist in exile. Differentiation replaced rivalry, and identity replaced estate.

That shift allowed a family to become a people. Survival came to depend on shared memory, distinct roles, and collective endurance. The covenant moved through people rather than property, and the biblical story never narrowed again to a single bearer.

For nearly two thousand years, Jewish history unfolded within that framework. Without land, Jews carried blessing as portable identity—education, law, ethics, aspiration. Children were blessed for what they might become, not for what they would inherit. That model sustained continuity across dispersion, persecution, and renewal.

History has turned again.

Since 2008, a plurality of world Jewry lives once more in the land of Israel. Concentration has returned. Land, sovereignty, and inheritance are tangible again, not symbolic. The Jewish people find themselves in the inverse position of Parshat Vayechi: no longer learning how to survive without land, but learning how to live with it again after centuries of absence.

Jacob understood that blessings and inheritance had to change in order for brothers to live together in the diaspora. This moment demands a parallel act of wisdom. The task of this generation is to pass on collective and individual inheritances which will hold both realities at once: rootedness in the land of Israel alongside the moral, intellectual, and spiritual capital forged in exile. The next generation must receive blessings that affirm individual potential and an inheritance that binds those differences into a shared future.

That synthesis—blessing and land together—is the challenge of our time.