The story of Joseph is the longest sustained personal narrative in the Bible. It is a life told end-to-end—youth and jealousy, betrayal and exile, moral clarity under pressure, reversal of fortune, and reconciliation. Jews have lived inside this story for millennia and drawn from it lessons about love misdirected, loyalty earned, leadership forged, and fate revealed only in retrospect.

It begins, uncomfortably, at home.

Jacob’s overemphasis on Joseph—his public favoritism, symbolized by the coat of many colors—fractured the family. It was not Joseph’s dreams alone that enraged his brothers, but the hierarchy their father imposed. Love, unevenly expressed, curdled into resentment. That resentment escalated to violence. The brothers nearly killed Joseph, then sold him into slavery, persuading themselves that exile was mercy.

And yet, the terror of the pit became the opening move in a larger design. Joseph’s descent—into slavery, into prison, into obscurity—ultimately saved thousands from starvation, including the very brothers who betrayed him. The Torah insists on an uncomfortable truth: human cruelty can coexist with divine purpose, without being excused by it.

Over time, the transformation that matters most occurs not in Joseph, but in Judah. The brother who once proposed selling Joseph later rises to moral leadership. Faced with the potential loss of Benjamin, Judah offers himself instead. Ultimatelty, kingship does not emerge from brilliance or dreams, but from responsibility and loyalty. Judah learns what Jacob failed to teach early: leadership is love with a wide visual field.

But this is not the only Joseph story in the world.

Yusuf and Zulaykha: A Different Emphasis

In Islamic tradition, Joseph is Yusuf, and his story unfolds with different texture and purpose. The Qur’an (Surah Yusuf) adds layers absent from the biblical text. Where the Bible does not even name Potiphar’s wife, Islamic tradition gives her a name—Zulaykha—and an entire inner life.

Her attraction to Yusuf begins as physical longing, but in later tradition becomes a spiritual ascent. Love itself is refined—from desire for beauty to yearning for the divine. This is not biography alone; it is allegory.

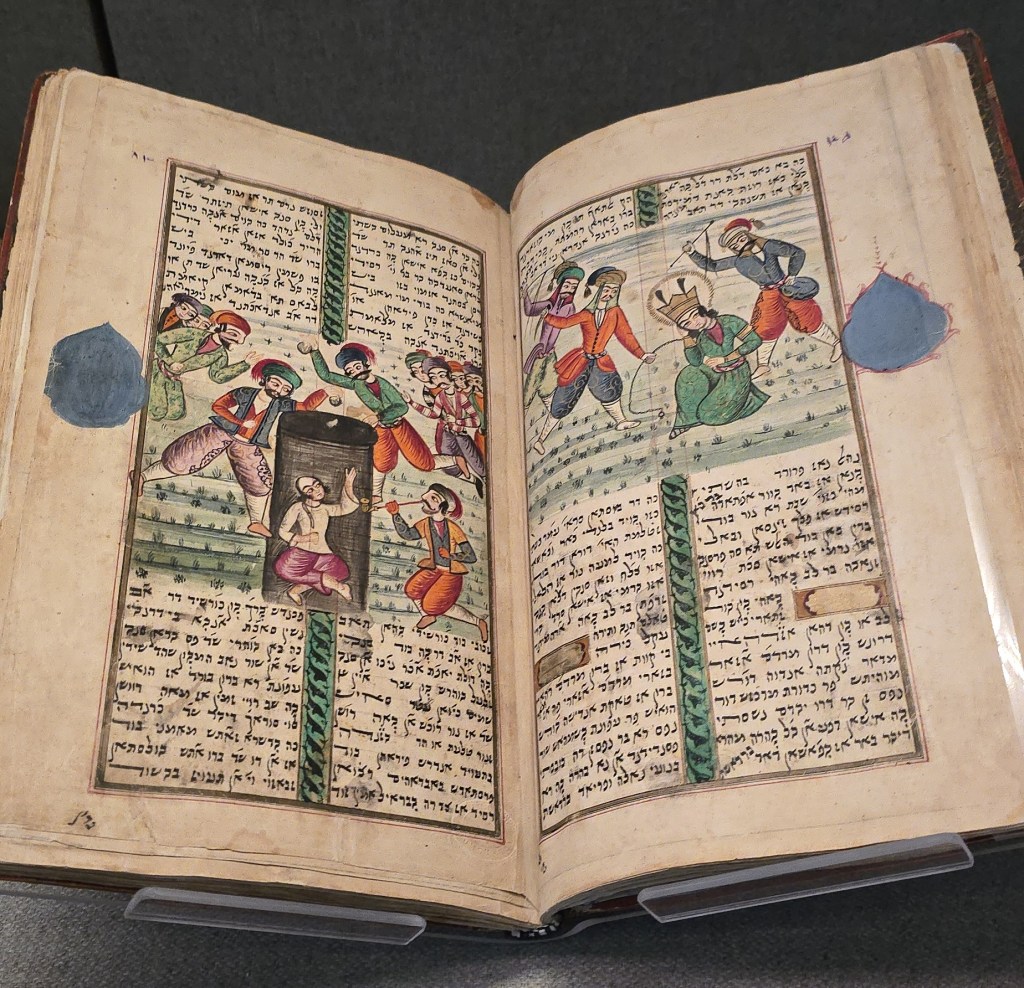

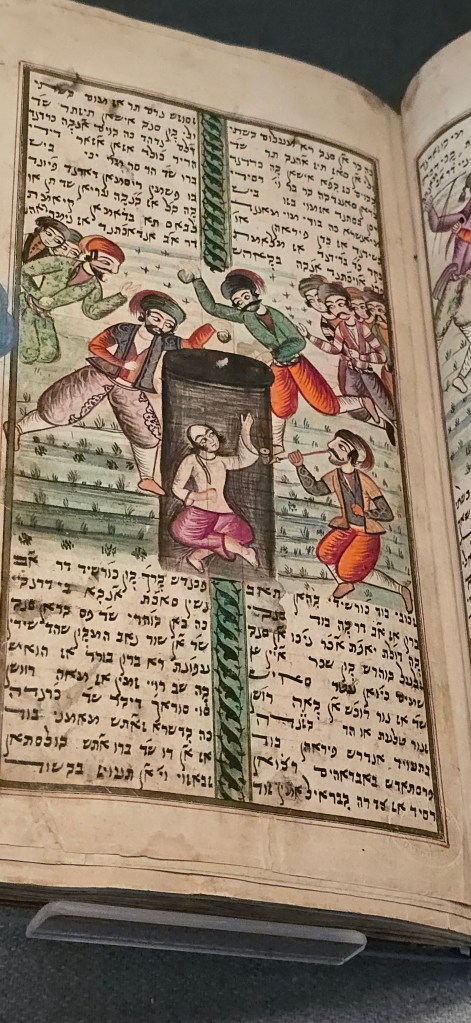

Persian culture preserved these layers visually, through extraordinary manuscript art that does not merely illustrate scripture but interprets it.

One remarkable manuscript—now on display at the Grolier Club from the collection of the Jewish Theological Seminary (until December 27, 2025)—shows Joseph cast into a well. The details are arresting. Joseph has lost not only his coat of many colors, but his hat and shoes as well—status stripped away piece by piece. The brothers even drop rocks down on him.

One figure stands apart in the drawing. At the bottom of the scene, a brother sits almost contemplatively. His hands alone are painted with henna, marking higher status. He smokes a long çubuk (copoq)—a dry-tobacco pipe, not the classic Persian water-based hookah—an unsettling detail as Joseph languishes in a dry well below. The image quietly foreshadows hierarchy, survival, and reversal. Even in betrayal, the future is being seeded. This must be Judah, on the side of the well with his five brothers from mother Leah, who is destined to help Joseph out of the pit and rise to fame himself.

Other images in the Yusuf cycle go further still in the manuscript. Women cut themselves upon seeing Joseph’s beauty (image 70 from Surah Yusuf 12:31). Zulaykha is said to lose her sight from longing for him (image 128). Beauty becomes dangerous, overwhelming, transformative. The Islamic tradition does not deny desire; it seeks to discipline and redirect it.

Two Traditions, One Origin

For Jews, Joseph’s story is about dreams and reversals, exile and return, family rupture and national survival. For Muslims, Yusuf’s story adds a meditation on beauty, temptation, and love’s ascent toward God. The Islamic telling emerged nearly two thousand years after the Jewish forefather lived. It is not wrong; it is different.

What matters for us today is that these differences did not need to fight. The stories coexist without trampling on the other.

The same characters—Jacob, Joseph, the brothers—carried distinct lessons without cancelling one another. No one is frozen forever as a villain. Jacob loved poorly but learned. The brothers failed catastrophically but changed. Judah rose. Sacred storytelling, at its best, refuses to eternalize blame.

That restraint is precisely what feels absent today.

Stories, Power, and the Present

The Holy Land, sacred to both Jews and Muslims, is no longer widely treated as a shared inheritance, but as a zero-sum possession. Hamas openly declares that Jews will be wiped out. Clerics in parts of the Islamic world speak in timelines of Jewish disappearance due to their being “enemies of world peace.” This is not interpretation; it is incitement. It rejects the Joseph model, in which history bends—slowly and painfully—toward survival, accountability, and reconciliation rather than annihilation.

And yet, Islamic civilization itself offers another precedent. Islam historically made room for Jewish continuity—absorbing biblical figures, preserving Jewish prophets, and allowing traditions to dovetail rather than collide. Yusuf did not replace Joseph; he walked alongside him. Zulaykha did not negate Potiphar’s wife; she deepened the moral inquiry. Reverence did not require negation.

That capacity still exists.

If Joseph teaches anything durable, it is that sovereignty, survival, and holiness are not insults to one another. Jews returning to and governing their homeland need not be read as a theological defeat for Islam. They can be understood, instead, as another chapter in a long, shared story—one that does not deny difference, but refuses extermination as destiny.

The question is whether we choose that inheritance again.