From the earliest chapters of the Hebrew Bible, we encounter a recurring theme: human beings trying to reach God through offerings. Noah offers thanks after the flood (Genesis 8:20–21). Abraham builds altars wherever he senses God’s presence (Genesis 12:7–8, 13:18). And in the first tragic sibling story, Cain and Abel each bring a gift to God—hoping to be seen, heard, loved (Genesis 4:3–5).

The Torah gives us the parameters of worthiness: a true offering rises.

Abel’s gift from the firstlings of his flock is accepted—traditionally understood as being consumed in heavenly fire (Genesis 4:4). It ascends upward like smoke from a perfectly tended sacrifice. Cain’s offering—of lesser quality—remains inert. No ascent. No connection. It is not merely ignored; it is a theological dead end, carrying the terror that one’s prayers may not only go unanswered, but may reflect back one’s own internal inadequacy.

That anxiety, that existential dread, echoes generations later across the Parshas of Toldot and VaYeytze.

Isaac’s Consuming Blessing

Jacob, urged by his mother, disguises himself as Esau in an elaborate plan to secure Isaac’s blessing (Genesis 27:6–29). Isaac eats the carefully prepared meal and, in a moment echoing the sacrificial imagery of Cain and Abel, pours out a blessing so full that when Esau arrives moments later, Isaac declares he has nothing left (Genesis 27:33–36). It was an all-consuming offering. Nothing remains.

Esau’s reaction mirrors Cain’s ancient rage. Spurned, overshadowed, convinced the divine pipeline has bypassed him, Esau vows murder (Genesis 27:41). The pattern repeats: the rejected one turns violent against the brother whose offering has “risen.”

Jacob’s Panic: A Blessing Built on Lies?

And so Jacob flees at his mother’s urging – that same person who had directed him deceive his father. Jacob runs both from Esau’s wrath and from the unbearable question gnawing at his soul (Genesis 27:42–45).

Was his mother’s plan a failure?

Did he truly deserve his father’s blessing?

Was it legitimate if it was obtained through deception?

Was he the new Abel—accepted and uplifted—or Cain, offering something that looked fine on the outside but was internally rotten?

Jacob had already exploited Esau’s hunger to purchase the birthright (Genesis 25:29–34), then deceived his own blind father to secure the blessing (Genesis 27:15–23). He must have wondered whether the blessings he secured, built on trickery, would end like an unburnt sacrifice—never rising, never accepted, destined to collapse under their own falsehood. Perhaps this moment was not a perfect echo of the sacrifices to God by Cain, but marked by the intentions and actions between people, with the uncertainties and fragility such interactions forever carry.

Was Isaac’s blessing a dead letter?

The Ladder: When Heaven Answers the Question

Then comes the dream at Bethel.

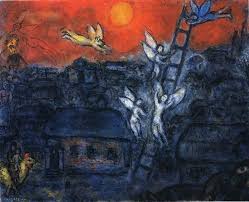

A ladder planted on earth, its top reaching into the heavens, with angels ascending and descending (Genesis 28:12). A strange image on its face. Many divine characters at a single time and place, moving in remarkable choreography.

The angels rising—those are the offerings, the intentions, the gifts Jacob has made, confused and imperfect though they may be. They ascend like the smoke of Abel’s sacrifice. And the very same angels descend—carrying blessing back down. Not new angels. The same ones. The same act, the same intention, returning in kind.

This is the divine reply Jacob so desperately needed:

Your offering was accepted. Your intent was seen. Your blessing stands.

Jacob Wakes with Calm

Jacob awakens transformed: relieved, inspired, grounded (Genesis 28:16–17). He WAS afraid. No longer. He understands the dream not as a prophecy of future events but as confirmation that his past actions—flawed in execution but upright in intention—had been received as a worthy offering.

So Jacob does what his ancestors always did in moments of divine clarity: he offers something back to God, establishing that site as sacred and vowing a vow of service and eternal charity (Genesis 28:18–22).

The Lesson: Intent Rises

The Torah’s message from Cain to Jacob is not that action is irrelevant. Far from it. But action without intention is inert—like Cain’s cold, unrisen offering. Intention, even wrapped in human imperfection, can ascend and draw God’s response.

Jacob’s ladder teaches that what rises from the heart returns as blessing. The smoke goes up; the angels come down. The offering is accepted; the blessing is confirmed.

Intent and action. Purity and performance.

That is the spiritual physics the Torah reveals—first in a field with two brothers, and then on a lonely night with a frightened man who finally learns he is worthy.