Jewish tradition returns again and again to the image of the tree. Sometimes it appears strong and fruit-bearing. At other moments it is reduced, cut back, or left without water. The image endures because it carries history within it—growth shaped by interruption, life that continues through constraint.

The prophets reached for this language when ordinary description failed them.

“They shall be like a tree planted in the desert, that does not sense the coming of good.” – Jeremiah 17:6

“Let not the barren one say: ‘I am a dry tree.’” – Isaiah 56:3

The statement reframes the moment. What looks final and foreboding is often incomplete. The future has not yet spoken.

That tension—between appearance and essence—finds a physical echo in the hills west of Jerusalem, where Yad Kennedy rises from the forest. The memorial marks a life interrupted mid-growth. John F. Kennedy’s presidency and life ended before its natural arc could unfold, and the monument holds that sense of unrealized promise. Surrounded by trees planted in rocky soil, it resembles a tree stump, and invites reflection on lives cut short and on continuity carried forward by those who remain.

Jewish history has unfolded along similar lines. After the destruction of the Second Temple, Judaism reorganized itself without sovereignty or familiar institutions. Across centuries of dispersion, it adapted under pressure, preserving learning and community in constrained forms. Growth did not disappear; it compressed, waiting for conditions that would allow it to expand again.

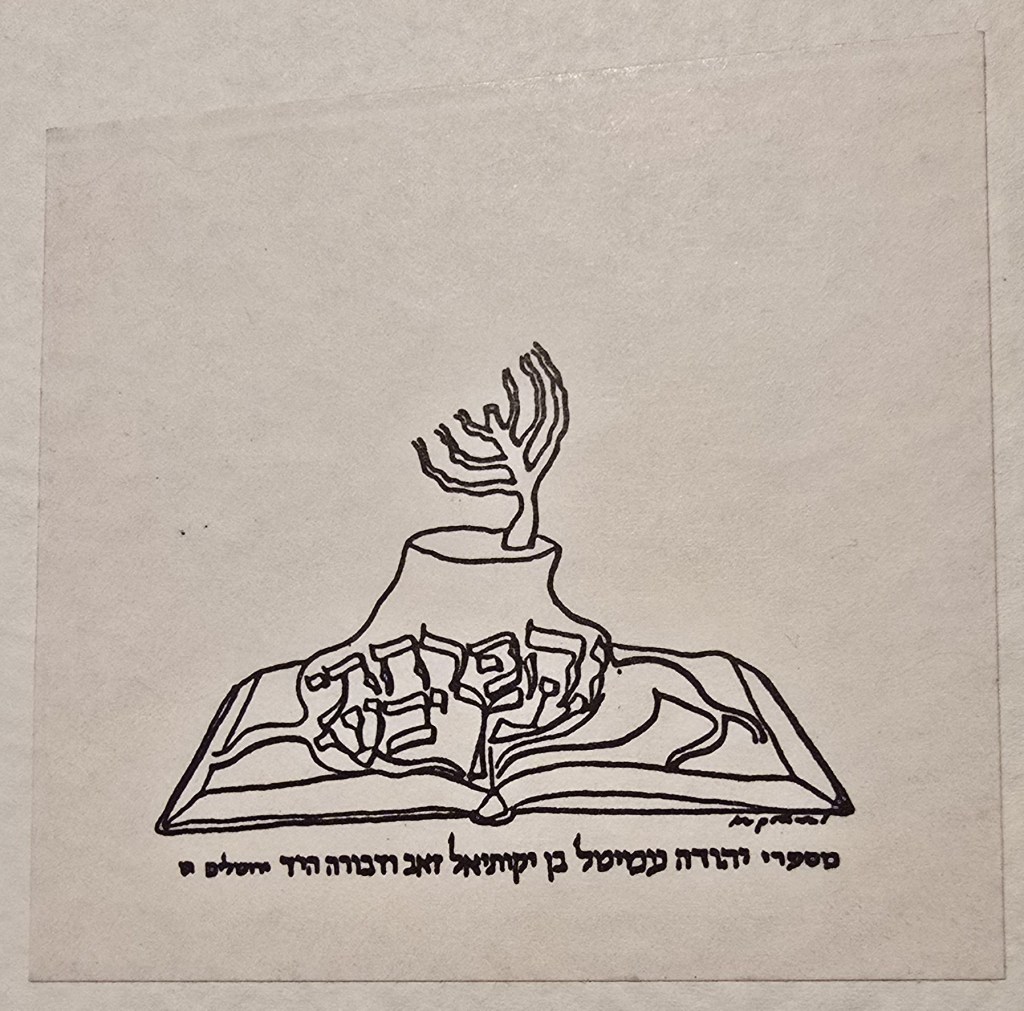

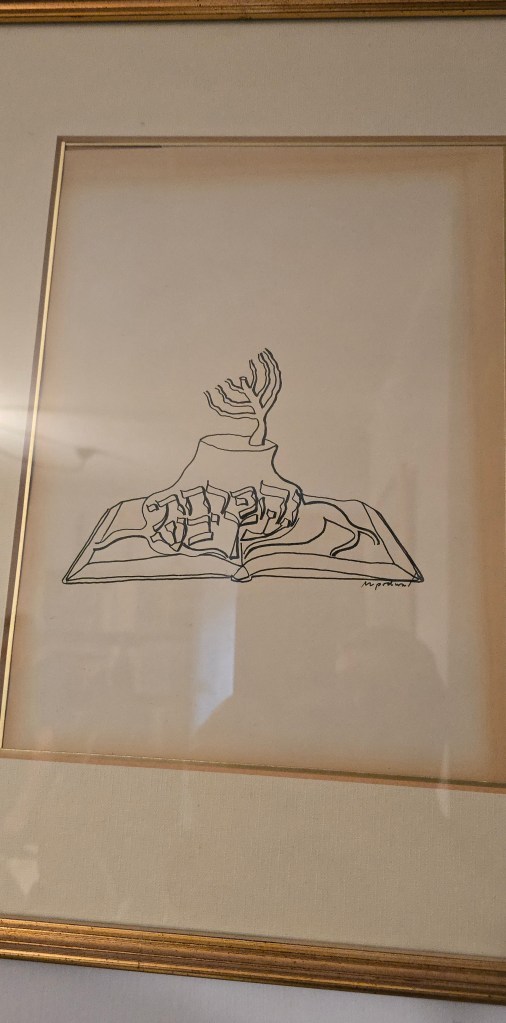

This persistence appears vividly in the work of Dr. Mark Podwal (1945-2024). His drawings return repeatedly to the Jewish tree—scarred, truncated, shaped by time. The branches rise unevenly, carrying memory in their grain. Life continues without erasing what came before. Growth is real precisely because it bears the marks of history.

That image resonated deeply with Rabbi Yehuda Amital (1924-2010), founding Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva Gush Etzion. A survivor of the Holocaust, Rav Amital rebuilt his world through Torah that could hold rupture and responsibility together. His leadership reflected patience, moral seriousness, and a belief that renewal emerges gradually from damaged ground.

Podwal once gave Rav Amital a drawing of a truncated Jewish tree—reduced in form, yet unmistakably alive, blooming with the promise of a renewed Judaism. The rabbi transformed the image into a small sticker and placed it inside the books of his personal library. Every volume bore the same mark.

The image spoke directly to his life’s work. Rav Amital played a central role in rebuilding the Gush Etzion community after it was destroyed in the 1948–49 War of Independence, a war in which he fought shortly after moving to the land of Israel after his family was slaughtered in Auschwitz. In the hills south of Jerusalem, homes had been razed, residents killed or expelled, and the area left barren. The return after the 1967 Six Day War was careful and deliberate, rooted in learning, faith, and responsibility. A community grew again where one had been cut down.

Each time Rav Amital opened a book, the image reinforced that lesson. Torah study itself became an act of regrowth.

That insight extends far beyond one community.

In the Land of Israel, Jewish roots run beneath history itself—through exile and return, ruin and rebuilding. Torah and Jewish presence were never uprooted from this land. They were compressed, covered, narrowed to fragments. Learning continued in small circles, in whispered prayers, in constrained spaces. At times the surface appeared barren. Beneath it, roots remained alive.

This is why Jewish life and learning in Israel carry a distinctive quality of reemergence. Yeshivot rise where silence once prevailed. Communities form on ground that held ruins. Torah is studied again in places where the chain of learning was abruptly broken. To the unobservant eye, it can appear improbable—as though life has emerged from wood long dried. To those who understand the depth of Jewish connection to this land, to the Jewish texts which form the basis of Judaism, it is recognition rather than surprise.

The dry tree was never dead. It was waiting.

Jewish continuity does not require ideal conditions. Where roots reach deep enough, water is eventually found. Growth resumes in forms shaped by everything that came before.