For Americans and Israelis, a summer vacation in Europe is almost instinctive. A relatively short flight offers a world away—new languages, different currencies, distinct cuisines. The joy is in the immersion: wandering museums, hearing street musicians in centuries-old plazas, staring up at Gothic spires, and feeling the weight of two millennia of history.

But the summer of 2025 was different. The walls of Europe’s cities told a darker story.

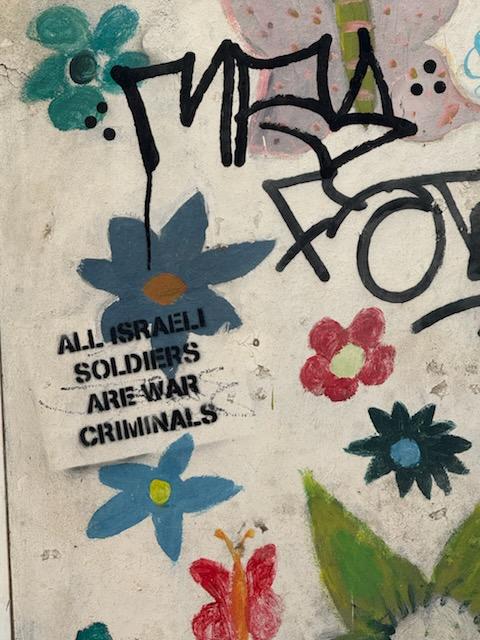

Alongside the usual student slogans and political tags were messages aimed squarely at one people and one country. Anti-Israel graffiti was everywhere—not just Palestinian flags but slogans in English declaring ” Smash Zionism” and “all Israeli soldiers are war criminals.” The words were not about policy disputes or borders. They were echoes of the Hamas charter, demanding the eradication of the Jewish state.

This was not the first time Europe’s streets had carried such messages. A century ago, it was pamphlets, posters, and shop signs. In the 1930s, “Kauft nicht bei Juden”—“Don’t buy from Jews”—was painted on storefronts. Nazi caricatures and blood libel imagery were plastered in public squares. These were not fringe ideas—they were mainstreamed into the civic landscape, normalizing antisemitism as part of public discourse.

Today’s slogans are more fluent in the language of modern activism, but the purpose is the same: to strip Jews of legitimacy and belonging. In the 1930s, the Jewish store owner was framed as a threat to society; in 2025, the Jewish state is framed as a threat to world peace. Then as now, the goal is erasure—economic, cultural, political, and, ultimately, physical.

What makes the present moment particularly jarring is its setting. The graffiti appears on the same walls that tourists pass on their way to see memorials to Europe’s murdered Jews. A plaque in the street may commemorate Jews deported to Auschwitz, but the wall above it proclaims “From the river to the sea,” a slogan advocating the removal of the Jewish State altogether. The contradiction is almost too much to process: “Never Again” in bronze, “Again Now” in spray paint.

Europe and the United States remain the last major powers to hold off on recognizing a Palestinian state somewhere in the Middle East. But that resistance is softening—not from a careful appreciation of the challenges of creating a peaceful, democratic state alongside Israel, but from the pressure of chants and hashtags lifted from jihadist manifestos. Politicians are not being persuaded by policy papers; they are being worn down by the relentlessness of street-level messaging and its seep into mainstream politics.

For Israeli and American Jewish tourists, the graffiti is not abstract. It’s aimed at them, personally. To walk through a city square and see your country branded as genocidal is not just uncomfortable—it’s alienating. It says: We know you’re here, and you’re not welcome IN HEBREW.

The tragedy is that many of the cities now hosting this wave of messaging were once vibrant centers of Jewish life, wiped out in living memory. The graffiti is a reminder that antisemitism, like the paint itself, seeps easily into old cracks, clings to old walls, and waits for the right political climate to dry in place.

There was scant commentary on the streets about the antisemitic genocidal group Hamas that launched the war. When it appeared, it was very small and seemingly in reaction to pro-Palestinian paint. It was a tank-versus-switchblade graffiti street brawl. The conflicts in Ukraine, Sudan, Myanmar and elsewhere were nowhere to be seen.

In the summer of 2025, Europe’s walls have become more than stone: they are mirrors that reflect not just the continent’s history, but its willingness to embrace its darkest periods. A reminder that the high brow culture frequently sinks in moral depravity.